Graphic: Elena Scotti (Photos: Getty Images)

The wife has fallen—metaphorically and literally. Collapsed at her husband’s feet, she clasps her hands in abject penitence and burrows her head in the hollow of her arms. The sleeves of her white blouse are blotted with red, mirroring the crimson wallpaper; both imply the presence of her sin. Meanwhile, the patriarch slumps in a chair, his face wearily vacant. But his anger manifests at the spokes: he clutches a message in his hand—presumably evidence of his wife’s infidelity—and, with his shoe, grinds a miniature of her lover. The elder of the couple’s two daughters regards the scene with shock as her house of cards crumbles, a symbolic reiteration of the marital fracture.

The scene belongs to a triptych of somber-hued oil paintings by English artist Augustus Egg that debuted at the London Royal Academy of Arts in 1858. The work, now collectively referred to as Past and Present, depicts a narrative of domestic and moral tragedy, rendering with great gloomy solemnity the sexual fall of a middle-class Victorian woman, and the abiding dissolution of her family. Characteristically Victorian in his heavy-handed reproof, Egg’s depiction of squandered feminine virtue was by no means avant-garde with its commitment to didactic realism. Egg lets his viewers know the stakes—that in fact, we’re bearing witness to an annihilation. By swapping duty for illicit pleasure, this woman has tumbled from her seat as the uncorrupt keeper of the hearth. The fallen woman embodies negation: She is perceived according to her unfathomable, villainous lack. It is, moreover, very important where this crisis takes place: the parlor, the most weighted of Victorian domestic spaces.

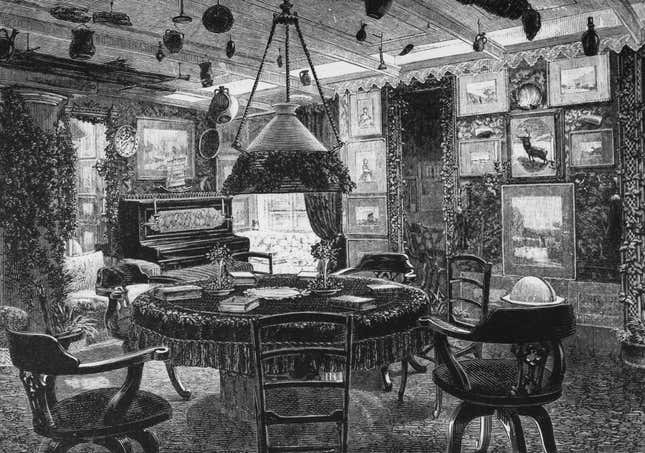

Egg’s contemporaries would have understood the parlor as the practical and ideological locus of the household—and so, the most evocative in the context of domestic rupture. This is bourgeois anguish: terrible, but elegantly situated. Even with its rococo revivalist touches—the gilt mirror, for example—the aesthetic is comparatively minimalist. Victorian parlors often heaved with patterned textiles, furnishings, and knick-knacks, but little material gluttony is apparent here. Instead, a handful of choice items sit comfortably, and with meticulous symmetry, atop the mantle. The gilt mirror hangs just above the fireplace, flanked on each side by a painting and a portrait of either the wife or her husband. It is, altogether, a discerning arrangement; one might call it tasteful, perhaps even restrained.

In my mind’s eye, a Victorian parlor takes the shape of an antique Anthropologie, an aggressively charming space, with its every corner fit to glut the senses—all while promoting itself as the perfect expression of beauty and ease. In fact, Anthropologie’s website features a page titled “A Modern Parlor,” where whiffs of historical context couch the brand’s contemporary, delicately rustic variation on the Victorian gathering space. Treating the parlor as a recuperated concept insinuates its obsolescence. But while it no longer prevails as the hallmark of middle-class refinement—many of us don’t keep a parlor, or even have the space for one—its accompanying ideologies hold fast. Domestic comfort remains the province of femininity; media dedicated to the arts of hosting and decoration seem to appeal, first and foremost, to women. Moreover, we populate our more informal living spaces—the den, the family room—with the same intimate and individualized signifiers that the Victorians privileged: family portraits, sentimental tchotchkes and, to foster connection with the natural world, flowers and houseplants. Even the most aesthetically minimalist living quarters cast a profusion of overlapping meanings: who one is, who one loves, who one wants to be.

This is bourgeois anguish: terrible, but elegantly situated.

The refinement of Egg’s parlor also belies its metaphorical bulk. We can just make out the paintings hanging on its wall, and they swell with ham-fisted symbolism. On the left, The Fall portrays Adam and Eve’s exile from the Garden of Eden, and on the right, Clarkson Stanfield’s Abandoned depicts a shipwreck. You might anticipate the rest: the wife’s portrait hangs beneath Adam and Eve, while the husband’s likeness is aligned with catastrophic desertion. The patterned crimson wall looms in the background with erotic menace, as if drenched with the depravity attributed to the wife. By contrast, the green carpet recalls The Fall’s lost Edenic paradise—here, the wife lays prostrate, as if resisting the penalty for her squandered virtue. She will also be banished from her safe haven.

Egg, clearly, is not one for understatement. He furnishes the parlor of Past and Present so that its every cranny hums the painting’s grim thematic tune. And what is a parlor without its mistress? It’s a fantasy punctured, a domestic center that cannot hold. Without the housewife’s chaste ministrations, the parlor harbors no intimacy, no promise of heteronormative joy. It is, finally, just a room. Everyone is present in Egg’s painting—husband, wife, daughters—but nobody is at home.

During its initial appearance, Past and Present was arranged so that the parlor scene hung between the second and third paintings, rendering it the narrative core of the series. It was proffered as a clarifying flashback, a view of the splintering moment inscribing a bleak future. Five years pass, and, as Egg emphasizes, everyone suffers. In one scene, the banished wife huddles by the bank of the Thames, cradling a spindly-legged baby: perhaps the result of the affair, and perhaps dead. The lover has ostensibly forsaken her, and her exile from home’s genteel security is permanent. Now, mother and child dwell in a space imbued by economic and sexual precarity (Victorians would have apprehended the dockyard’s association with sex work). In a separate, simultaneous scene, Egg portrays the daughters, grief-stricken in the wake of their father’s recent death. This loss, coupled with their mother’s estrangement, renders them orphans. The room absorbs their lonely solitude, its affect summoned by the empty, narrow bed and the closeness of the chamber. Their parents’ portraits—the ones that previously hung on the parlor wall—now preside in the sisters’ garret, supplying meager company. There is no returning to the parlor, Egg suggests; its harmony, once blighted, can never be recuperated.

The shape of this morality tale makes cultural sense. Invested as they were in the notion of separate spheres, the Victorians regarded femininity as inextricably domestic. “[The] woman’s power is for rule, not battle,” writes the influential art critic John Ruskin in his 1865 treatise, Sesame and Lilies, “and her intellect not for invention or creation, but for sweet ordering, arrangement, and decision. She sees the qualities of things, their claims, and their places.” Home, then, was a woman’s domain; its local occupations of beautification and comfort were—per contemporary misogynistic theory—perfectly suited to her capabilities. Labor expectations were calibrated according to this notion of women’s different, and diminished, intellect. “Women… were responsible for deploying objects to create the interior space identifiable as ‘home,’” writes Thad Logan in her book, The Victorian Parlour: A Cultural Study. Without dispute, women’s work was paramount to the performance of bourgeois gentility; nonetheless, women were trivialized and bound by punishing gender conventions. The home was a sanctuary, but only its master occupied it by choice. “[Women] were, in some sense, its inmates,” explains Logan, “but they were also its producers, its curators, and its ornaments.” If a housewife was preoccupied with candlestick arrangement or the angle of an armchair, perhaps she was not merely designing her family’s stronghold—perhaps she was finding a way to bear her place in it.

The parlor prevailed by way of synecdoche; more than any other space, it embodied the very concept of home, and so demanded particular attention from its mistress. It was also the site in which every major life event was commemorated: births, marriages, and even funerals (thus the term “funeral parlor”). The setting for such ceremonial occasions required a corresponding dignity and finesse. “[Who] can define the pleasure that the numberless trifles in a well-garnished drawing-room may be made to afford to the eye, and thus to soothe and satisfy the mind?” entreats Lucy Orrinsmith in her 1878 meditation on the subject, The Drawing-Room: its Decorations and Furniture. Every detail—from woodwork to fireplace to draperies to varied tchotchkes—offered the opportunity to express one’s socioeconomic prosperity. Unsurprisingly, the parlor was often the most lavish room of the house, and the least functional; instead, it enacted the silent labor of signification. A gilt mirror, like the one hanging in the Past and Present parlor, communicated wealth; it also made the room look bigger. Patterned ceramic tiles served as an economical artistic touch for Victorians decorating on a budget. And, ever the colonialists, nineteenth-century Britons chased exotic ornamental touches: Persian rugs, Japanese embroidery, Chinese fans. “A Japanese effect in a drawing-room may be produced at but slight expense,” advises Orrinsmith in her chapter on walls and ceilings. Apparently, even strident racism could not mask the superiority of foreign arts and crafts.

Of course, for many, the pleasure of cultivating a swanky parlor was predicated—at least somewhat—upon its visibility. And if a Victorian housewife wanted to show off the room’s William Morris wallpaper or its new marble mantelpiece, she required visitors. Most families would receive guests in their parlor; it was a public space, although its entrants were as curated as its furnishings. Tradespeople would not be received here, affiliated as they were with the grit of the workaday world, and servants only crossed the threshold when asked to do so by a member of the household. When a family was neither receiving callers, nor entertaining, the parlor was reserved for their privacy of repose and recreation. Regardless of context, the exclusivity of this space shored up the hierarchical class ideologies so pervasive in 19th-century society. If one enjoyed the luxury of having a parlor, they also enjoyed the power of adjudicating social access by determining who was welcome and whose presence was inappropriate.

This illusion of unmarred, intimate, and financially robust domesticity stood on rickety legs. In particular, it required two hefty buttresses: vigorous material consumption and the labor of house servants. Victorians with means enjoyed an unprecedented ability to purchase commodities—to indulge in items that were not necessary, but pleasant. Decorative fans, Venetian bottles, painted tiles: these objects did not so much foster “home” as they represented it. Writers like Orrinsmith and Mary Eliza Joy Haweis disparaged the practice of mass accumulation in their treatises on decorating, but often the temptation was too great to withstand. “The characteristic bourgeois interior becomes increasingly full of objects,” writes Logan, “cluttered…with a profusion of things [which]…participate in a decorative, semiotic economy.” Parlor decor was likely to mirror the natural world, to assert itself as a bucolic-inspired paradise. The sensory overload of wax flowers and taxidermied birds might send you into a panic, but at least you’d have a pretty place to faint.

“To be healthy and happy, we must have beautiful and pleasant things about us,” declares Haweis in The Art of Decorating. Her views on homemaking were published in 1881, following The Art of Beauty (1878) and The Art of Dress (1879) and prior to The Art of Housekeeping (1889). (In a polymathic power move, Haweis also studied and published books on medieval poet Geoffrey Chaucer.) As Logan observes, Haweis harbored sordidly classist notions of what beauty required—her description of London’s “bloated and purple face ‘flower-girls’” in The Art of Housekeeping turns the stomach—and so perhaps it is fitting that she conceives of it as vacantly pastoral: “If we cannot have trees and flowers, mountains and floods, we can have their echoes—architecture, painting, textile folds in changing light and shade.” For a middle-class Victorian Londoner, retreating into the parlor amounted to an act of sumptuous denial. She was utterly protected—from the sooty factories churning out merchandise, the ragged, starving people who worked in them, and the Thames River, stinking with shit and garbage. She was even shielded from her own servants, whose assiduous and grueling work underpinned this mirage.

Like any dichotomy, the concept of public and private spheres is manufactured. And despite the Victorians’ ideological reliance upon it, it was impossible to maintain. Even Ruskin muddies the waters in his effort to articulate the sanctity of women’s duties: “[Wherever] a true wife comes, this home is always round her. The stars only may be over her head; the glowworm in the night-cold grass may be the only fire at her foot; but home is get wherever she is.” Sesame and Lilies is an exercise in gender essentialism, and yet, in his effort to render femininity as inviolably domestic—a house is not a home; a home is a good woman—he admits that no boundary is sound. Even the most virtuous woman will be exposed to the wider, wretched world: She will step into it, or it will scout out her parlor and find her sitting by the fire.

To the contemporary ear, “parlor” might sound like a terminological heirloom. It signifies, after all, a domestic space that has long since diminished in import. We are more likely to invoke the word in the context of the commercial sphere, perhaps in reference to a funeral or tattoo parlor. Meanwhile, the home has undergone a tonal shift towards ease and informality. As both the telephone and the automobile grew more ubiquitous, it became unnecessary for a woman to hold court for persons of business; instead, she could place a call or drive to the store. Or perhaps she couldn’t—because she was occupied with her own professional pursuits. By the turn of the twentieth century, vast numbers of women were seeking work outside the home. Cultivating a pretty bower for one’s husband was never universally satisfying. Now a woman could forego the seclusion of homemaking without stirring a scandal; she might even reject marriage altogether.

Simultaneously, the expense of urban living forced many to accept more modest accommodations. In America, it began to seem impractical—extravagant—to limit the usage of a room to rare and specific occasions. Available space needed to perform a function; only the wealthy could afford to consecrate square-footage and lock it behind a heavy door. The parlor, then, was eliminated through acts of domestic repurposing; its relevance has been dwindling for so long that even historical texts wax poetic on its disappearance. As Russell Lynes writes in a 1963 article for American Heritage, “[The] parlor became the sitting room for all of the family every day. Its furniture became more comfortable, its atmosphere more relaxed; the children were allowed to do their homework at the center table under a gas fixture which shed its bluewhite light from a ceiling chandelier.”

And yet, the parlor’s ideological echoes remain. Victorian gender essentialism makes for an able time traveler; it imbues contemporary discourse on home decorating and hosting. Whatever latitude women enjoy, we have not shed our domiciliary associations. Now HGTV targets women with open floor house plans: suitable, the channel reminds us, for entertaining guests. An episode is likely to conclude with scenes of a cozy house party, communicating the host’s eagerness for domestic expression. Architectural informality has not quashed rituals of home and hearth; rather, it has brought about an adapted schema, one of practiced, coiffed casualness. Implicitly, women are urged to twinkle and beam as the well-heeled priestesses of “LIVE LAUGH LOVE.” We might gather our friends for a leisurely hang in the kitchen, where the granite countertops gleam and the Anthropologie dish towels are crisply folded. At the height of its influence, the parlor masqueraded as four walls and a ceiling—in fact, it is a nagging, long loitering ghost, haunting us with its arcane shibboleths, its whispered moans of how a woman ought to be.

Victorian gender essentialism makes for an able time traveler; it imbues contemporary discourse on home decorating and hosting.

Ultimately, and as Egg’s Past and Present anticipates, the parlor cannot withstand the overdetermined symbolism imposed upon it. As surely as it signifies an immaculate world apart, it also becomes its opposite: voluptuous, debased, and secret. Writes Logan, “While the parlour was an intensely respectable setting for the performance of bourgeois life, the very heart of a self-regulating middle class, there was another side to this space: it was the cave, the den, the lair of woman.” In the 19th century, even the most economically and racially privileged woman was subject to the Victorians’ neurotic gender binaries, and their various implosions. A white and well-mannered Victorian woman would be celebrated as an exemplar of virtue: the gentle and retiring counterpart to man’s brash, frenetic energy. But as Logan notes, “the idea of Woman” was fraught with paradoxical connotations; she was impossibly good and, just maybe, impossibly debauched. Prevailing ideology understood femininity as tethered to sexual otherness—other, that is, from man and all that he was recognized to be. White maleness constituted normativity; it followed, then, that women were sites of erotic mystery and, necessarily, suspicion. And so we remain, it seems. “What women want”—a query born from an ostensible effort towards masculine empathy—still garners performative exasperation (what we want, after all, is too inconvenient to acknowledge). What’s more, any gender that deviates from straight cisgender maleness begets the hegemonic anxiety of intolerant confusion. Against all reasonable evidence, patriarchy insists that only white male heterosexuality is to be trusted.

Past and Present inscribes this instability in its parlor scene, exploded as it is by the wife’s fallen body, lustful and ashamed. The home was a woman’s sacred canvas, the parlor its most precious swath, where, with flourishes of domestic intuition, she—and her servants—created a comfortable respite from the masculine world of commerce. But a parlor that holds a body holds its desires. They are everywhere present: in the marble mantelpiece, the gilt mirror, and the coal dust, swept into the bin. Look too closely at its pretty fragments, and home might seem a frightfully alien place.

Rachel Vorona Cote is the author of Too Much: How Victorian Constraints Still Bind Women Today, which was published in February 2020 by Grand Central Publishing. She also publishes frequently in such outlets as The Nation, the New Republic, Pitchfork, Literary Hub, and Hazlitt, and was previously a contributing writer at Jezebel. She lives in Takoma Park, MD.