When Did the Windsors Decide to Become 'Normal' Parents?

In Depth

This year, Father’s Day and the birthday of William, Duke of Cambridge, fell on the same Sunday. Kensington Palace went all out on Instagram, with pictures of William and his three children piled cheerfully together on a swing; another of the four rolling around on the grass happily; and—perhaps most arresting of all—an intimate shot of William embracing his father, both smiling, Charles’s head resting fondly on his son’s shoulder. All were the work of Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge, who frequently takes the photos shared on the royal family’s social media. These are the type of photos that could be hanging on the wall in any middle-class house. But it’s a break with much of the history of the British monarchy, when family has often been about power rather than intimacy, endlessly complicated by concerns of dynasty, and the absolute last thing monarchs wanted was to appear “normal.”

The narrowing of kinship to focus on the nuclear family is a modern phenomenon generally, and for anybody with any kind of wealth—i.e., the aristocracy and the monarchy—family was bound up with property and influence, which guided the decisions of royal parents in Britain and elsewhere. For instance, in the middle ages, “Edward III placed his dozen children in the households of prominent members of the nobility, a practice followed by numerous other medieval monarchs,” Carolyn Harris noted in her history Raising Royalty. It was a handy trick for strengthening connections that was also practiced by other nobles in the medieval period, fostering out their children for periods. And of course, throughout the long history of monarchy, daughters were married off, shipped away to far-flung corners of Europe. One of Edward III’s daughters, Joan, died at 14, caught by the Black Death on a journey to marry a Castilian prince.

Queens raising their own children could be complicated. Harris explains in Queenship and Revolution in Early Modern Europe that the Tudor queens were closely involved in their children’s upbringing, but the Stuarts tended to establish “separate royal households for their children and entrusted their upbringing and education to trusted deputies.” Part of the problem was that, in an era where royals married each other for dynastic reasons, queens were imported foreign princesses not necessarily seen as appropriate influences on the future king. It was particularly thorny for Henrietta Maria, wife of Charles I, a Roman Catholic from France as England was building toward its Civil War; the question of just how much influence she had over her own children was a vital political issue that could determine the religious future of Great Britain.

The royal parent-child relationship has been impossibly complicated by the fact that raising a successor often means creating a rival: training someone to rule and then requiring them to sit around, waiting for you to die, is a real tricky proposition, and monarchs have had to hand off just enough power to keep their heirs busy without undermining their own sovereignty. A frustrated and still dependent heir could be a real problem, as Henry II learned in the 1170s when his three sons rose in rebellion against him with the assistance of their mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine. Family squabbles were matters of international importance.

Even as kings had their wings clipped by successive revolutions, this has persisted. Queen Elizabeth II technically has custody of her great-grandchildren, including George, Charlotte, Louis, and even Archie. That’s the legacy of the profound familial dysfunction of the Hanovers. The future George II angered his father George I so much that he banned his heir from the court and retained guardianship of his grandchildren; he and his wife had to plead to see their kids once a week. This played into the politics of the time: “George’s household became the centre of opposition to the king’s policies, and Leicester House–George’s residence in London–became the meeting place for members of the Whig faction in government,” who opposed the conservative Tories, said History Extra. (George II and his eldest eventually replicated the exact same dynamic.)

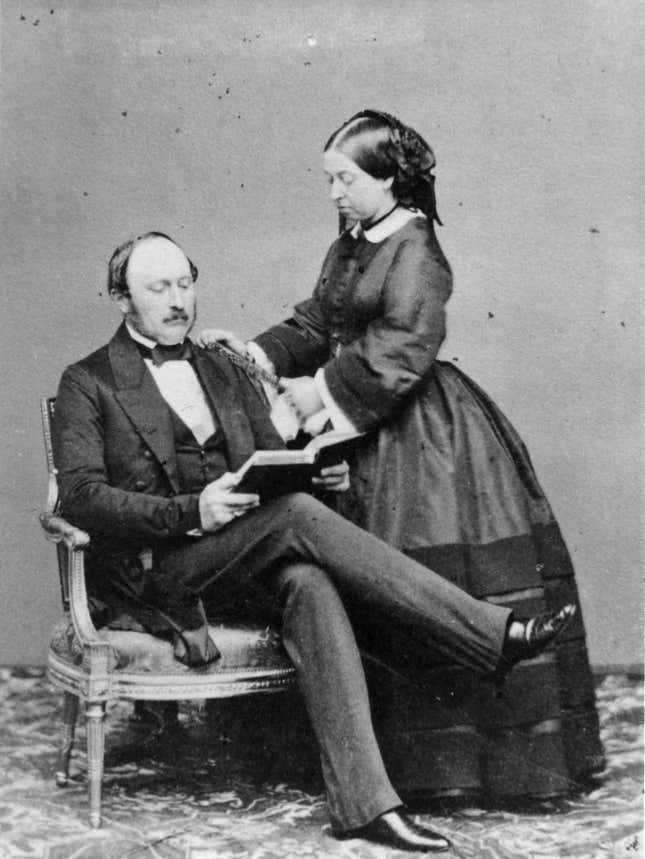

The domestic arrangements of the royals began to shift under Victoria and Albert, who really pioneered the notion of “the royal family,” revamping the whole institution for an era where they had soft power rather than much in the way of actual constitutional authority. (Partly to slide out from under the lingering disruptable stink of the Hanovers.) They positioned themselves as the moral heart of the nation, aligning themselves with the burgeoning British bourgeoisie. In their private lives they enthusiastically embraced the new medium of photography for intimate family snapshots, but they also disseminated this imagery to the public, portraying Victoria and Albert as the ultimate prosperous, buttoned-up Britons—the prototypical Victorians.

But at the same time, Victoria and Albert weren’t simply sentimental figures on a Christmas woodcut, either. While the crown was tightly constrained in the United Kingdom, monarchies across Europe still had plenty of power—and so they set about advancing their vision of liberal constitutional monarchy by marrying their children and grandchildren into the various dynasties of Europe, attempting to steer global politics through marriage.

Even as the rest of Europe’s monarchies toppled and dynastic marriage fell away—Philip was technically born a Greek prince, but they lost the throne when he was a child, leaving his family adrift across the continent—royal parenting still hewed to very formal scripts, even as the approach fell out of fashion more broadly. Elizabeth II breastfed, but when she returned from a royal tour in 1951, she publicly greeted her toddler son Charles with a somewhat stilted handshake and a cheek kiss, and Philip’s bewilderment with his son’s emotions is, at this point, fairly notorious. But as the monarchy has become ever-more symbolic over the 20th century—and the culture less formal—the Windsors have had to stay in step.

It’s over the last two generations that the modern royals have really bought into the closer-knit nuclear family. It’s a sincere desire: First came Charles and Diana, with their concern for providing as much of a “normal” life as possible—which is a big caveat—and now Kate, who is certainly from a wealthy background but not the aristocracy, with their long history of distant childrearing practices. She and William have made a point of doing the school dropoff and made time for other workaday moments of parenting that were not, historically, a royal priority.

At the same time, the royals make choices about what facets of themselves to put on public display, and they’ve made a choice not merely to cultivate a closer family life, but to present themselves as a conventional nuclear family, surrounded by an array of extended relatives, to deliberately disseminate that imagery through social media. They aren’t exactly foregrounding their nannies and other domestic help in the picture. They talk about the difficulties of homeschooling in lockdown; Kate not only posted a picture of her youngest, Louis, doing an adorable rainbow hand craft—she followed it up with a pair of pictures with jokey “Instagram vs. Reality” captions, positioning herself as just another mom (albeit, one raising the future king of Great Britain) surviving the daily chaos of parenting. This is the adaptability of the Windsors once again, weaving majesty with the prosaic. They still deal in fairy tales, but in this case, the fairy tale is about a particular vision of family life.