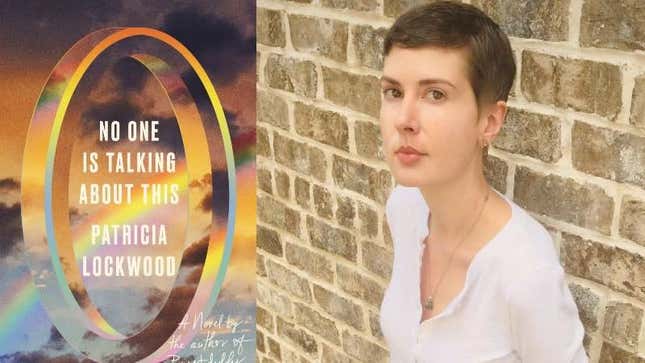

Don't Fear Patricia Lockwood's Internet

In Depth

In the spring of 2017, Patricia Lockwood was hiding from her husband, avoiding an impending move to a new home. “You know when you’re a kid and you’re moving house, you just hide in a closet with one of your books?” she says over Zoom from her home in Savannah, Georgia, cradling her laptop in bed. “I was basically doing that.” She was reading the novella Mrs. Caliban by Rachel Ingalls, the story of a stagnant housewife who encounters and falls in love with a bizarre aquatic creature, when she realized she could write about the “supermundane.”

“For me, that included the Portal,” Lockwood says. “It actually largely took place in the Portal. I was like, all right, she writes about making out with some escaped lizard guy, I’m going to write about whatever the hell we’re doing online.” The Portal is what Lockwood calls the internet in her new novel No One Is Talking About This. The novel asks an important question: What the hell are we doing online?

If there’s anyone who might be able to tell us, it’s Lockwood. For the past decade, Lockwood has established herself as a uniquely weird, irreverent voice in contemporary literature, including the unforgettable “Rape Joke” published in 2013 and her funny memoir about being raised by a married Catholic priest, Priestdaddy. Last year she published one of the more terrifying personal essays about having covid-19 for The London Review of Books, the symptoms of which, including “debilitating neuropathy in her hands,” she is still experiencing.

“I had an entire day of extreme paranoia when they titled the piece ‘Insane After Coronavirus’,” Lockwood says, paranoia being one of the neurological issues she faced after contracting covid-19. “I was like, what if it’s not okay to say that I was insane after coronavirus! My God, will I be canceled over my coronavirus!”

But it’s Lockwood’s Twitter account, where she publishes surrealist one-liners and dispatches to more than 80,000 followers, that has solidified her as a lighthouse for original thought. Her posts about the worst Beanie Babies in existence and casual asides that she dreamed of a “substance called hypercum,” are always blessedly out of sync with the news and scandals of the day. Her most famous tweet to date still may be when she plainly asked The Paris Review Twitter account, “So is Paris is any good or not.”

The unnamed narrator of No One Is Talking About This is a loose outline of Lockwood herself, an internet-obsessed woman famous for a post that simply read, “Can a dog be twins?” She travels around the world giving talks about “the Portal,” an internet that is “an avalanche of details,” where everything has been “decided by a sky in long black judge robes.” The first half of the novel twists and turns like a rollercoaster ride designed for the extremely online, moving through the narrator’s experience of the portal’s wonders and horrors in a fragmented, highly quotable (or Tweetable, really) style. “NOT my america, a perfectly nice woman posted,” she writes. “And for some reason she responded, ‘damn, I agree…we didn’t trap george washington’s head in a quarter for this.’”

“It’s like sidewalk drawing in Mary Poppins,” Lockwood says of what it feels like to enter the internet as she describes it. “You jump in, you’re on that carousel, and you’re wearing a hot new outfit.”

Unlike her previous books, Lockwood said she wrote most of No One Is Talking About This on her phone, often while traveling. “It’s very impressive actually,” she says, laughing. “This internet novel I wrote on my phone.” You can test your own cursed Twitter addiction by how well you can identify Lockwood’s obscure references sprinkled in the text: a misguided woman who says she doesn’t care if a child got eaten by an alligator in an attempt to critique white privilege, “caucasianblink.gif.”

The language of the internet and how it warps the mind is the central concern of No One Is Talking About This. Even as Lockwood’s narrator exists as a famous voice within it, she often thinks that someone else is dictating her own thoughts to her, and bristles against the homogeneity of her feeds. “The mind had been, in its childhood, a place of play… It had also once been the place where you sounded like yourself,” the narrator remembers at one point. “Gradually it had become the place where we sounded like each other, through some erosion of wind or water on a self not nearly as firm as stone.”

“The book is a kind of a pushing against the communal mind, against the herd,” Lockwood says. She says she gets uneasy when she finds herself using the same language that everyone is using at the same time that they’re using it. When she first got to Twitter, she says, she felt like she was often called to the position of “observer” simply because she didn’t know “why anyone is doing what they’re doing.” “Everyone is adopting this slang, why are they using this?” Lockwood asks. “Or I would see people adopting, a lot of times, Black American slang. And I was like, why are they doing that? Are they doing this in an ironic way?”

“A poet is a person who, fundamentally, their experience of the language is strange,” Lockwood says, joking that she still doesn’t think she “reads correctly” after a childhood of near-sighted reading. In the book, the narrator is exasperated in the face of family members using “horny emojis” without context, or the seemingly collective agreement to say things like “SHOOT IT IN MY VEINS” or “normalize.”

“I think a lot of people will just adopt a new language without ever considering that,” Lockwood says. “And I’m not necessarily speaking in denunciation of that tendency, I think that’s what human beings do. That’s why we have the language that we have.”

No One Is Talking About This is divided into two parts, and while the book’s first half is a funny, disorienting snapshot of online’s expanse designed for those already well acquainted with social media, the second half finds Lockwood’s narrator largely offline. In a sharp plot turn that mirrors Lockwood’s personal life, the narrator’s pregnant sister is told her baby has Proteus syndrome, a rare genetic condition. She gives birth in a Catholic hospital in Ohio, a state with hostile abortion laws and induction restrictions, and the reality of the baby’s long-term future is unclear. Suddenly, the immense amount of time the narrator has spent in the Portal seems horribly misplaced. “Oh, she thought hazily, falling rainwise like Alice, finding tucked under her arm the bag of peas she once photoshopped into pictures of historical atrocities, oh, have I been wasting my time?” Lockwood writes.

“I would sometimes experience—when I would be editing or reading through all the way—the shock of the sincere that you get to in the second half,” Lockwood says. “And I was like, man, should I take out all of these really, really sincere things? And of course, the answer is no, don’t do that.” Writing about her niece, Lockwood says, was a physical impulse. “It was not something that I could really deny,” she says. While she acknowledges there are many fictional elements to the book, she says that “at a certain point, you thrust off that fictionalization, that curation of things that makes them look perfect, and you just enter into the real.”

at a certain point, you thrust off that fictionalization, that curation of things that makes them look perfect, and you just enter into the real

Where once the novel’s material seemed boundless, the pregnancy grounds the narrator in the physical reality of hospitals and waiting rooms. Suddenly she exists alongside her sister in a state where “the governor’s pen was constantly hovering over terrible new legislation” that would put the baby and her sister’s life in danger, arguing with their anti-abortion father. Lockwood was raised in a staunchly anti-abortion, Catholic household, which she writes about in Priestdaddy, and says she can still remember all the slogans, all the bumper stickers.

“But even as a person knowing how much rights had been eroded, particularly in states like Ohio, I was still unprepared,” Lockwood says. “I was unprepared for the shock of that moment, and I didn’t know how to navigate that moment or help my sister navigate that moment. And I think that really says something, because I’m fairly well versed in those laws and the history of those places, and if I don’t know what to do with it how are other people going to know?”

Rather than recount the internet’s scroll for hours, Lockwood’s narrator then experiences the wonder of a baby experiencing life for the first time and the creation of a mind even as extraordinary circumstances threaten its creation. Her niece delights in knowing her parents’ voices, in musical instruments and amusement park rides. Lockwood magnifies life’s simple joys, severed entirely from the online world she previously described, to reveal their power in a baby’s eyes. “What is a human being?” the narrator asks herself, over and over. “What is a mind?”

“What we were initially told about this pregnancy, about this child, was so dire that the question became what is a human being, what is a mind that potentially will produce, as they told us, no thoughts?” Lockwood says, of the recurring question. “That [she] will have no sense of numbers, may not recognize our voices, that she may not be able to eat on her own. All of these things that you think are so crucial to personhood, what is beyond, what is there if you don’t have those things?”

“What has been scrolling down the inside of my mind? Am I simply a sort of mass of impulses among many?” she asks. These are the book’s crucial questions. “It came to the fore when you’re existing in this kind of bodiless place where you’re not even sure you’re thinking your own thoughts, and then suddenly you’re presented with a question of what is a human being.”

It’s easy to scowl at the internet as a totally ruinous place, to simply critique an already fragile life lived largely on social media. The internet is where users go to ostensibly waste the time of “real life.” Who we are on the internet is not who we really are, our morals and thought patterns are eroded by new lingo and ideas suddenly popular, and we are all worse for swimming in its waters.

And No One Is Talking About This clearly captures social media’s chaos, and how it can fundamentally change people. But the book identifies the boundaries between an online world and the real world outside of it without turning into a simple indictment of the internet. Lockwood’s narrator, when confronted with the trauma of her sister’s pregnancy in the “real world,” does not simply detach herself from the internet and cast it off aside forever, welcoming a life logged off. Rather, the internet stays with her, in poignant and darkly comic ways. At one point the narrator suggests how nice it would be to take her newborn niece to the Cincinnati Zoo. Her sister, who appears to be on the brink of tears, responds, “We can also mourn Harambe.”

“Harambe is more meaningful to Cincinnatians than it is to other people!” Lockwood reminds me, laughing, when I reference this passage. She says that what you learn in the Portal, “the sort of wallpaper on the inside of your mind,” stays with you when you’re dealing with the urgency of real life.

“I think that one of the main things that people want to know is, is this thing that we have been doing worth doing?” Lockwood says. “Has it unfitted us for the business of real life, real situations like this? And I don’t know that you can become unfitted for those situations. Your body knows what to do. Your body is ready when they come up.”