'Je t’aime et je t’adore': The Intimate Romance of Eleanor Roosevelt and Her 'Dearest'

In Depth

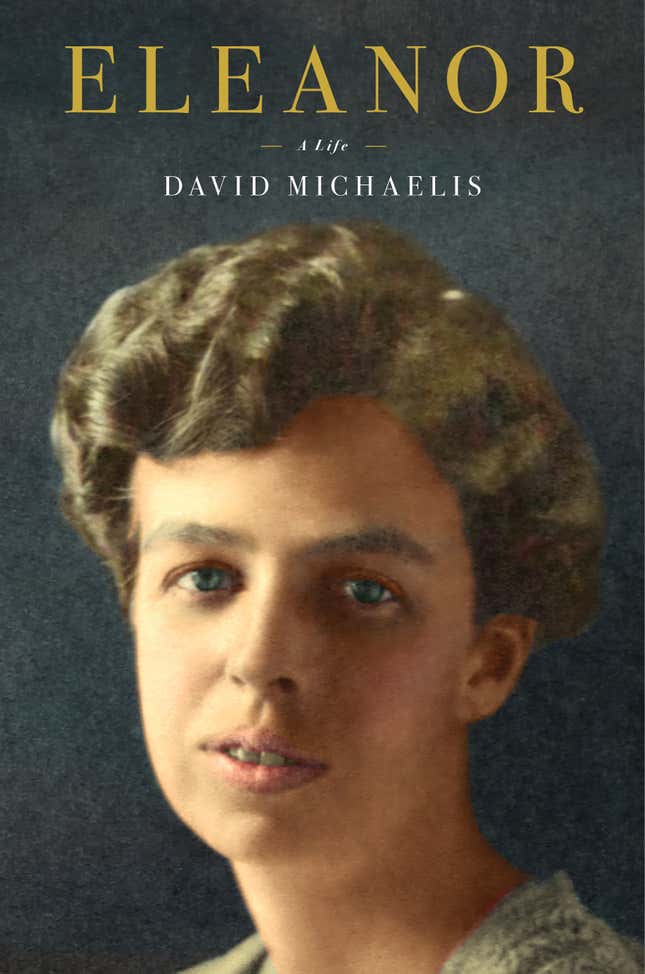

Image: AP Photo

Covering the Gov. Alfred E. Smith presidential campaign in 1928, Lorena Hickok could not have imagined risking professional suicide for Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt, who was supporting her husband’s political ally. It was bad enough for a reporter of Hick’s stature to be assigned the woman’s beat. Yet the more she had studiously avoided Mrs. Roosevelt as a subject, the more smitten she was by Eleanor. For the first time in two decades, a colleague found reason to warn Hick about getting too close to her sources.

The hardboiled reporter could admire the professionalized Eleanor as “an outstanding civic and welfare leader” who personally maintained Spartan standards of modesty and austerity. Yet it was the very stuff of women’s pages—ER’s $10 dresses and lunches at drugstore soda fountains—that caught at Hick. One day she noticed that Eleanor kept her long, thick hair contained within the fine black strands of an elasticized hairnet. To Hick’s horror, the net crimped just enough of Eleanor’s forehead to vary the shape of her face. Of all the reporter’s scribbled impressions of Eleanor’s looks (“very plain”), clothing (“unbecoming”), and commanding presence as mistress of the Executive Mansion in Albany (“a very great lady”), none told better how tightly contained Eleanor had kept herself—before Hick—than did the picture of a black hairnet gathered in the center of her forehead.

The day after Smith lost the 1928 election to Herbert Hoover, Eleanor invited Hick to East Sixty-Fifth Street. Hick went, of course, to interview Mrs. FDR, the Democratic National Committee’s Women’s Division generalissima, but the occasion seemed not to call for pad and pencil. Hick was flattered to find an elegant silver tea service laid out. There were cakes. No one else was expected. Eleanor poured as for a dear friend, smiling and chatting. To Hick’s further surprise, Eleanor had turned herself out elegantly. She even relaxed while being interviewed. “But,” sighed Hick, “the hairnet was still there.”

To Eleanor, Hick was “[a person] in whose soul there is no peace.” Born on March 7, 1893, in East Troy, Wisconsin, Lorena Alice Hickok was the eldest daughter in a family dominated by her father’s abusive drinking and chronic unemployment. Her mother made ends meet sewing dresses, but Anna Waite Hickok died of a stroke when Hick was thirteen, and her father, who had been inflicting beatings throughout childhood, raped Hick when she was fourteen. Addison J. Hickok surprised no one when he put his daughter’s pets to death. He later died by suicide. When Hick was asked to contribute to her father’s funeral expenses, she answered: “Send him to the glue factory.”

Leaving two younger sisters in East Troy, she worked in a boardinghouse and on a farm until she was taken in by her mother’s cousin in Battle Creek, Michigan, finishing high school there. After a year of college, she got herself a seven-dollar-a-week job on a Battle Creek newspaper—assigned, she later recalled, “to meet all trains.” One of them took her out of town—to New York City—in February 1918. For the next six months she covered city politics for the New York Tribune, taking from her first interview at Tammany Hall the lesson every fresh-faced reporter learns: stick to the questions. A glance at her notes afterward revealed that she had learned precisely nothing from or about “Silent” Charlie Murphy, while he “knew all about me.”

She lived every day for its deadline, a practice of turning bitterness to productivity: “There’s no other work that requires such devotion. It’s no game for physical weaklings. You go without sleep, without food. You have to completely forget your own self.”

High school classmates had named Lorena Alice Hickok most likely to become a famous suffragist.

She became the Associated Press’s star, its highest paid female reporter, covering such national sensations as the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby and the Walker-Seabury hearings that helped propel FDR to the Democratic nomination. Her fellow news hawks thought her the quintessential shoe-leather beat reporter, “soft-hearted and hardboiled,” her whole body “rippling with merriment” on a Prohibition story about drunk sewer rats; the tears flowing as she smashed out copy about Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s infant son. Colleagues noticed her beautiful legs, a peaches-and-cream complexion, arresting blue eyes; they recognized her as something different and special in a newspaperwoman—“quite a gal,” they told each other, and meant, in part, her audaciousness, but, still more, her excellence, her eye, her humanity. High school classmates had named Lorena Alice Hickok most likely to become a famous suffragist. For Eleanor, she was a midlife rule-breaker, and very quickly much more.

Within a month of FDR declaring for President in 1932, Eleanor was in full pursuit of romance. On the campaign train through the Southwest, she sprung Hick from the reporters’ pack, bringing her along to see Isabella Greenway. In Nebraska she teased Hick into following her into an eight-foot-high cornfield row and out the other end through a barbed-wire fence. Eleanor glided coolly through stalks and soft-iron strands into the adjacent pasture, leaving Hick puffing and panting, shawled in corn tassels, plucking rusty barbs from her silk stockings. She brought Hick aboard a plane that Eastern Air Transport had put at her disposal for a night flight. The pilot roared over incandescent Broadway, dipping at Columbus Circle, then turning northeast—out over the dark of Long Island. At 6,500 feet, the cold night city sparkled in the windows, and the smoke rising from factory chimneys over the Jersey meadowlands reminded Eleanor of the Doré Bible illustrations from her upriver childhood. “What a lot can happen,” she remarked to Hick, “in the short space of one’s life.”

Eleanor encouraged her new sidekick to follow along as she attended a funeral in Potsdam, near the Canadian border, then pulled Hick onto a side trip along the St. Lawrence River to the site of a New Deal power project that would connect the Atlantic Ocean with the Great Lakes. The streets there showed no sign that the country was engaged in a momentously important presidential contest. “Franklin is going to be dreadfully disappointed if he loses this election,” she told Hick. “For a while he won’t know what to do with himself.”

After dinner with friends of Eleanor’s, they boarded their night train to New York. One lower berth was free. Eleanor spread herself along the long, narrow couch opposite.

Over Hick’s protests she insisted, “I’m longer than you are.” Adding with a smile: “And not quite so broad.”

They talked through the night, Eleanor revealing to Hick Franklin’s admiring warnings (“Better watch out for that Hickok woman. She’s smart”) and Tommy’s benediction (Eleanor’s telling response: “So I decided you must be all right”). She told the story of her Ugly Duckling childhood, her mother’s death and her father’s disintegration, touching lightly on Grandmother Hall, her drunken uncles and screwball aunts. Hick asked if she might write “some of that” in her next article about “Mrs. Roosevelt.”

“If you like,” said Eleanor. “I trust you.”

Inauguration morning dawned leaden and blustery—“a dark dour day, in one of the darkest, dourest hours in the nation’s history,” reported the columnist Damon Runyon, on loan from Lindy’s to democracy’s defining moment.

On the drive to the Capitol, Eleanor asked her predecessor what she would miss about life in the Mansion. White-haired Lou Hoover, who had made the President’s house monarchical by placing marine buglers on the stairs, replied that it was “the feeling of being taken care of” that she would miss most of all—the never needing to make travel arrangements. . . .

The crowd was massed twelve-deep on the curb as Eleanor and Lou Hoover rode past. The iron-colored sky would brighten for a moment; staring faces would pop in the shifting light—a woman with a child pushing to the front, a man snatching off his hat—but altogether they seemed to be waiting for someone to tell them what to do.

At the Capitol’s East Front, Eleanor’s husband of twenty-seven years took the Presidential Oath of Office, then turned to face the crowd of thousands which had gathered on the Capitol Plaza. He allowed a single gleaming smile, then mirrored the serious faces of the people as he delivered his message. It was time, said President Franklin Roosevelt, to face conditions boldly and honestly. He affirmed his own stark commitment to “speak the truth, the whole truth.” With steel bracing his legs and hips, he upheld the nation’s powers of survival and revival by remembering its fortitude and hope in dark hours past.

He chopped out his words like tomahawk throws. “Let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

Eleanor glanced at the crowds, and for a moment she took in their doubt like a mouthful of seawater—then felt calm newly ascendant when Franklin announced his intention to ask Congress “for the one remaining instrument to meet the crisis—broad executive power to wage a war against the emergency, as great as the power that would be given to me if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.”

All the waiting was over. The roar of purpose that greeted this suggestion—the biggest applause of the speech—renewed Eleanor’s faith in her husband’s power to reach through numbing despair to join people to his own self-assurance as it built through confidence and nerve to outright daring. “I always felt safe,” said Eleanor of the years just ahead, “when Franklin was in the White House.”

Upon entering 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue by the front door, Eleanor drew off her gloves, revealing the ring Hick had given her: a breath-catching sapphire encircled by diamonds.

She did not know where to conduct their interview for the AP, which marked the first time that the wife of a president in office would speak for publication. Her second-floor sitting room was the only place she could call her own, and for now there were only packing crates on which to sit.

She had taken Mrs. Hoover’s bedroom in the southwest corner and would furnish it with Val-Kill pieces and some easy chairs and a sofa by the fireplace. For her actual bedroom, she chose Mrs. Hoover’s dressing room, and for a bed would install a three-quarters daybed, also from the Val-Kill workshop. Her desk would stand in between sitting-room windows that looked onto the South Lawn and a hundred years of serial presidential plantings.

She was glad to help Hick with an exclusive. At least she had that much clout. That week, Sara Delano Roosevelt, mother of the thirty-second President of the United States, was featured in the red-bordered international proscenium of Time magazine. The story treated Eleanor as a minor nuisance, while extolling Sara’s exceptional closeness with her son. It was a lesson from an American success primer: when the son becomes terribly important, the mother gets the credit, stands proudly at her boy’s side, and the wife can find her own place to sit.

Time could mount her at the farthest point in the old family triangle, but the AP interview catapulted Eleanor into a future she would barely be able to catch up to in an unimaginable dozen years, let alone the next four. Starting on packing boxes in Mrs. Roosevelt’s second-floor sitting room, they ended in the bathroom—the only place, Eleanor and Lorena claimed, they could find privacy for a serious press interview. “Hardly the kind of thing one would do with an ordinary reporter,” objected one backstairs account, “or even with an adult friend.”

That night, in her room in the southwest corner of the White House, Eleanor confided to Hick: “My dearest, I cannot go to bed tonight without a word to you.”

She had marked her engagement book that day with single-word reminders: Capitol, parade, tea. For the 6:30 p.m. slot, she had inserted the one event of Inauguration Day that qualified as a recorded memory: “Said good-bye to Hick.”

“My dearest, I cannot go to bed tonight without a word to you.”

“I felt a little as though a part of me was leaving tonight,” she admitted. “You have grown so much to be a part of my life that it is empty without you even though I’m busy every minute.” These were “strange days & very odd to me but I’ll remember the joys & try to plan pleasant things & count the days between our times together!”

Getting into bed, Eleanor kissed Hick’s picture good night and repeated the kiss the next morning. That first of more than four thousand nights in the White House, she went to sleep with Lorena in her thoughts, repeating to herself their nightly endearment, Je t’aime et je t’adore.

From Eleanor by David Michaelis. Copyright © 2020 by David Michaelis. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.