That Shape He Can't Forget: The Bittersweet History of Diet Soda for Women

In Depth

Graphic: Elena Scotti (Photos: Getty Images, eBay, The Coca-Cola Company)

Tab premiered in 1963, in a textured glass bottle dotted with Space Age sparkles. An early ad from Mademoiselle showed a graceful hand wearing a pair of bracelets, reaching out for the drink from a peacock chair. “Doesn’t it make sense to be refreshed with sensible, modern Tab?” the ad asked. Nearly immediately, the Coca-Cola Company’s first diet soda targeted women specifically, promising to reshape their bodies.

And in October, when the company announced Tab would be discontinued, Coca-Cola maintained its commitment to the bit with a press release proclaiming that dropping the brand would “reshape” and “streamline” the company. The announcement was unsurprising: Tab made up just 1 percent of Coca-Cola’s sales in recent years. It’s also true that Coca-Cola invested relatively little in Tab over the decades because it was intended for only, or mostly, women; it was eventually packaged in a bright pink can and sold through decades of highly feminized advertising, which limited the brand’s appeal. Beverage companies have depended upon women consumers of diet products, but they’ve always wanted a larger audience. They’ve always wanted men.

Despite companies’ hankering for bigger sales, they’ve had trouble envisioning a different purpose for diet drinks than selling the image of slim women’s bodies. As a result, their pitches often fell flat.

Tab was a notable diet drink, but it wasn’t the first. That honorific belongs to Diet Rite Cola, which was launched in 1958 by Royal Crown Company. They developed Diet Rite as an option for diabetics and other consumers who needed to limit their sugar intake. Devoid of calories, it was first stocked among medicines rather than soft drinks, but focus soon shifted to the growing number of weight loss dieters nationwide. (Case in point, Weight Watchers incorporated in 1963.) Recognizing this growing consumer pool, ads promoted Diet Rite as the “Feel All Right” soda.

Sweetened with cyclamate and saccharin, Diet Rite boasted the taste of cola without sugar. In her history of artificial sweeteners, Carolyn Thomas called this “indulgent restraint”—that is, the ability to consume sweet foods, but without negative consequences, such as calories, weight gain, or tooth decay. This sugar-free proposition understandably worried the sugar industry. In response, Domino Sugar ads assured consumers that sugar provided an “energy lift” and was lower in calories than typical diet-friendly foods like apples, grapefruits, and hard-boiled eggs. They even produced their own sugar-centric “reducing” plans. Diet Rite advertising wasn’t afraid to hit back. Advertisements that ran in 1964 targeted both men and women with statements such as “Guilty of upsetting the sugar cart? We plead guilty” and “Have you tried the taste that’s got the sugar daddies howling mad?”

Sugar producers had reason to howl. Diet options comprised less than 1 percent of all soft drink sales in 1958, but Diet Rite rose to the number four soda within 18 months of its national launch, indicating a previously untapped market. Indeed, diet cola sales increased from 7,500,000 cases in 1957 to more than 50,000,000 in 1962. As a result, competitors launched a number of new offerings. After many months dedicated to “Project Alpha” and their quest for a diet soft drink, Coca-Cola launched Tab in 1963, the same year as Pepsi’s Patio, which was renamed Diet Pepsi in 1964. Coca-Cola’s Fresca joined the party in 1967.

All of these sodas weren’t necessarily intended for women consumers alone. For example, Diet Rite marketed to women, men, and children, all at the same time, and claimed that consumers appreciated the drink’s “delicious” flavor more than its low calories, making it a beverage suitable for every member of a health-conscious family. An ad campaign in the 1960s asked, “Who’s drinking all that Diet Rite Cola?” alongside images of women quizzically holding empty cases of Diet Rite, pleasantly flummoxed that their husbands and children had drunk it all “because it is by far the best tasting cola of all.” In 1969, Diet Rite TV commercials featured celebrity spots with Twiggy, Lena Horne, and John Havlicek of the Boston Celtics, thin stars specifically chosen because they “obviously don’t need to diet,” emphasizing Diet Rite as “so good even non-dieters drink it.”

Over the years, Tab also targeted primarily women with messages about weight loss and notions of conventional feminine beauty. The “Be a Mindsticker” campaign (which contemporary viewers rightly find super creepy) encouraged women to drink Tab in order to “stay in his mind with a shape he can’t forget.” Despite this focus on sticky patriarchal body-shaping (and shaming, too?), Tab’s pitch still addressed taste. Other ads questioned, “How can just one calorie taste so good?” Billboards decreed, “Tab tastes better than any diet cola.”

Early diet sodas’ combination of cyclamate and saccharin did taste similar to sugar, but the FDA banned cyclamate in 1969, based upon laboratory studies on rats that linked the substance with the development of malignant bladder tumors. This forced the reformulation of most diet sodas, resulting in drinks that tasted sweet, yes. Just like real sugar? Um, no.

Nevertheless, Tab devotees in recent decades described the drink’s flavor with words like: crisp and clean, citrus-like, and nostalgically tart with a slight bubble gum flavor. Others use phrases like “very, very sweet, with the aftertaste of furniture polish.” Different from options like Diet Pepsi, Tab wasn’t a knock-off version of another drink. Tab drinkers claimed that because the beverage was not a no-calorie version of a full sugar option, “it tastes completely chemical, a relief from the faux-sugary diet sodas that dominate the market.” Imitating nothing, Tab was its own original diet soda and for decades, a top-selling beverage.

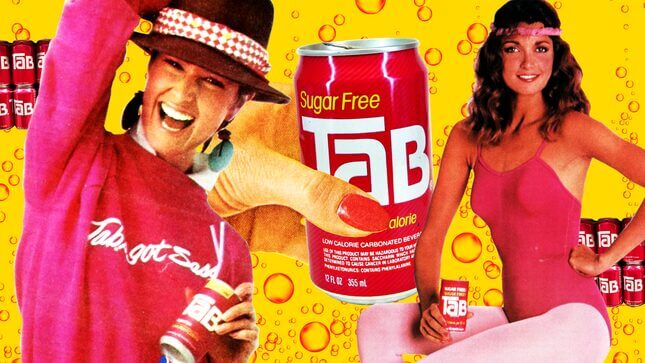

Coca-Cola today historicizes Tab as “a cultural icon in the 1980s.” It’s a truer story that Tab’s demise started then. In his history of Tab, media scholar George Plasketes described the drink as a “stepchild” and “a clinging orphan” that was put “on life support” and “gradually exiled toward possible extinction.” In late 1970s and early 1980s ads, Tab boasted itself “the beautiful drink for beautiful people,” attempting to message men as well, but without significant results. Tab ads in the 1980s zeroed-in on women with campaigns like “Tab’s got sass” and “Body by Tab,” featuring slim women in leotards and swimsuits.

Unlike Tab, which seemed entrenched in a women’s demographic, Diet Coke sought both male and female consumers, especially those who endorsed health, fitness, and appearances as part of a 1980s “yuppie” lifestyle. Coca-Cola executives mused that men wouldn’t buy Tab, given its identity as a diet drink coupled with years of heavily feminized advertising, but they might try Diet Coke, especially since it was being marketed as “incidentally” low-calorie. These executives knew launching Diet Coke in 1982 would “cannibalize some of the market for Tab,” but they did it anyway. Diet Coke launched with ads proclaiming, “You’re gonna drink it just for the taste of it,” and by the end of 1983, it was the nation’s best-selling diet soft drink.

Although Coca-Cola went after male consumers with Diet Coke, men (and broader culture) seemed to deem the beverage derisively feminine in later decades. For example, in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution an unidentified Coca-Cola executive declared that diet is a “four-letter word” for men, or at least those aged 16–24. That belief inspired Coca-Cola to try, yet again, to craft a non-diet diet soda for men.

Since the very beginning, diet soda development and marketing focused on taste and flavor, but starting as early as the 1990s, Coca-Cola went back to the drawing board to create an even better tasting sweetener for a diet soda for men—Coke Zero—which is one of the stories I tell in Diners, Dudes, and Diets: How Gender and Power Collide in Food Media and Culture. Coca-Cola assumed men demand full and satisfying flavor, compared to the at times unfulfilling and unpleasant aftertastes women have long accepted from diet drinks. And so, Coca-Cola sweetened Diet Coke with aspartame, while Coke Zero boasted a sweeter combination of aspartame with acesulfame potassium, referred to as “Ace-K,” a nickname befitting a winning quarterback, or maybe a Bond villain. As a result, Coke Zero offers more of the sweet taste and full mouthfeel of sugar itself.

Coke Zero launched in 2005, but Coca-Cola wasn’t alone in reconfiguring their sweeteners with bolder flavors intended for male consumers. After Coke Zero’s early success, a reformulated Diet Mountain Dew purportedly launched in 2006, followed by Diet Pepsi Max in 2007 and Dr. Pepper Ten in 2011.

While Coca-Cola sought to win over men (and maybe some women too) with the taste of Coke Zero, Diet Coke has leaned into its perceived feminization over the last forty years. Whitney Houston, Paula Abdul, and Demi Moore starred in Diet Coke commercials with feminine flair in the 1980s and 1990s. In 2013, Taylor Swift served as brand ambassador in a series of girly ads. That year Marc Jacobs also started a yearlong stint as Diet Coke Creative Director to celebrate the brand’s thirtieth anniversary. He created a trio of can designs, which he described as “whimsical, feminine, colorful, and fun.”

And yet, five years later, Diet Coke tried to reinvent itself when it comes to gender, again. In 2018, Coca-Cola unveiled a rebranded, but not reformulated, Diet Coke. They kicked it off with the company’s first Super Bowl commercial in twenty-one years. The rebrand was the result of two years of research and testing, necessitated by further declines in the soft drink market. In 2016, six of the top nine diet sodas saw a sales drop, including Diet Coke, long a best seller. Coca-Cola company executives described their efforts to transition Diet Coke from a woman’s diet drink to a “contemporized” millennial beverage for both men and women.

And yet, Diet Coke hasn’t been able to shake its feminized roots, which the brand itself seemed to openly acknowledge in a March 2020 commercial, “Drink What Your Mama Gave Ya.” The spot opens with two young men sitting at a table. As one takes a sip from a can of Diet Coke, the other derisively quips, “Diet Coke? Who are you, my mom?” The ad then flows into a tribute to not just moms, but spectacularized 1980s moms, dressed in turquoise jumpsuits, rib-high stone-washed jeans, and purple legwarmers over hot pink tights. Despite Diet Coke’s best efforts to reinvent itself as a unisex millennial beverage, its own advertising situates its glory days in the past—the particular past of Tab.

Some men have and still do drink Tab. Marty McFly orders one in Back to the Future; my own husband, a wrestler in high school and a bodybuilder in college, loves Tab. But despite its small, loyal fan base, Tab remained popular with primarily a niche demographic of college-educated, middle-class women who watched their weight. Although Tab embodied nostalgic, retro chic for a tiny slice of young fans, broader cultural trends and tastes changed. We don’t diet anymore, we’re focusing on our wellness and self-care. We don’t drink Tab, we’re sipping sparkling water flavored with “natural essences.” Despite such shifts (which may be much smaller than we think), Tab is worth remembering. As its chapter in the history of diet soda ends, Tab reveals how brands like Coca-Cola conceived of women as consumers, leaving a bittersweet aftertaste, once more.Emily Contois, PhD is Assistant Professor of Media Studies at The University of Tulsa. She is the author of Diners, Dudes, and Diets: How Gender and Power Collide in Food Media and Culture and the co-editor of a book on food Instagram.