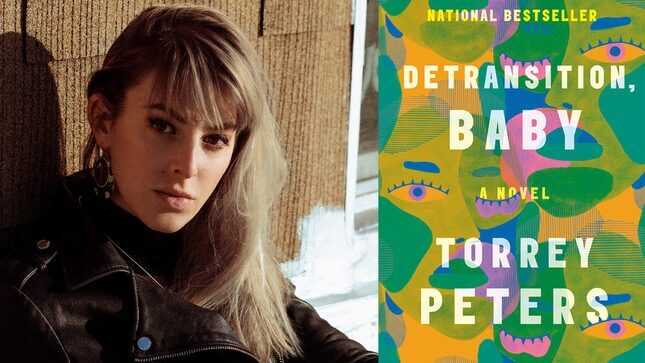

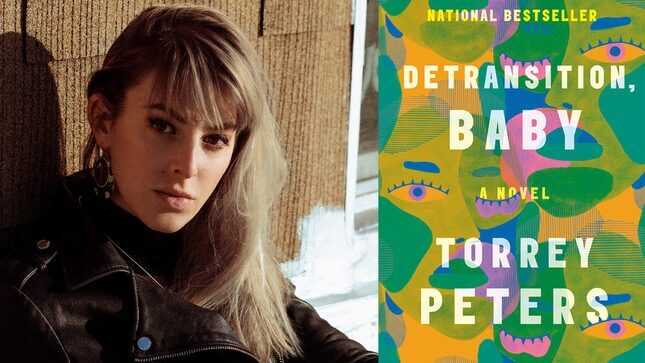

My friend and colleague Harron Walker once found it difficult to preface the force that is Torrey Peters. Now, here I am, repeating that confusion, at a loss for how to possibly describe a writer who refuses to be pinned down by other’s expectations. Her debut novel, Detransition, Baby, published in January, has been met with near-universal acclaim.

To understate the speed at which her writing bubbled up from the trans underground and onto the front page of the internet would probably be just what she wants. We laugh about as much, reminiscing about our first encounter, over a year ago now, during a (pre-pandemic) New York winter that was unseasonably warm. It was at the book club of a mutual friend, for a book we both hated, and then a subway platform past midnight, where we lingered longer than we should have, two total strangers bound up in a conversation about failure, trans motherhood, and a book deal she had just recently signed with Random House. This book deal, to be exact.

Time flies when you’re locked indoors.

Detransition, Baby serves as a sort of baptism for the fighting words—about transmisogyny, reproductive rights issues, modern queerness, Cuisinart mixers—that Peters would have at one point in her life would have just tweeted about. The book follows narrator Reese, a trans woman in New York City, who longs to be a mother. Suddenly, she finds herself once again in the orbit of her ex-girlfriend, Ames, who calls with unexpected news. Jumping back and forth in time, Detransition, Baby charts the course of their lives and relationship, up until it imploded—after Reese had an affair and Ames de-transitioned to live as a man. Years later, his boss and new girlfriend, Katrina, is shocked to learn that not only is she pregnant with Ames’ child, but he once lived as a trans woman. In the chaos and unraveling of their beliefs about the world, themselves, and the women they want to be, Reese is stunned to learn, as is Katrina, that Ames wants them all to raise the baby, together.

I recently hit Peters up to catch up on our lives as of late, and of course, the whirlwind experience of finally publishing Detransition, Baby. But also just to kiki with one of my favorite provocateurs in the solar system.

Our conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

JEZEBEL: I feel like this is the perfect springboard because I’m going to call out Harron Walker right now.

TORREY PETERS: Please start out by canceling her, I’ve been threatening it for a long time.

One of your first big interviews was with Them, and Harron, in 2018. The frame of that was a lot about how to write about a trans author—do them justice. I wanted to ask you about this quote, a couple of years later, and see how you feel. “With so much trans writing, I can read the headline and the first sentence and stop there, I already know what it’s about. I know how it’s going to end. I don’t want the profile to be like, hey, here’s Torrey. Torrey is gorgeous and smart. Great job, Torrey. Great job on self-publishing. You know? What’s interesting there? What is worth saying about that?”

Now that you’ve had the book published and you’ve been giving all these interviews, have your feelings about the “trans interview” changed for you?

Now I’m very into being told that I’m gorgeous and smart. So that’s one change. But otherwise, I was trying to get out of being framed in these very saccharine, predictable ways of talking about trans people, where they’re not given the chance to be fully human. They’re given the chance to be inspirational stories, to be a kind of content. And so I still think that if I’m treated like the story is, “Torrey overcame in the publishing industry,” that’s actually a pretty boring story. I think the fact is I wrote a big book, and I hope it is a good book that brings up challenging questions, that people can challenge me about.

Now I’m very into being told that I’m gorgeous and smart

Cis-told stories of transition rely on that same “overcoming narrative,” but I actually read Detransition, Baby as not about resilience or overcoming, but a falling apart of these character’s prescribed ways of living. More specifically, I was interested in how you framed that unraveling for a character like Ames, who presents to Katrina a grand struggle of how hard it is to be a white trans woman in New York, and how white trans women don’t have a community: They lost their elders in the AIDS crisis and then they got super niche online and distanced themselves from each other. It all came off profoundly selfish to me.

You’re right. I think that the book is about the unraveling of these different characters’ narratives and coping mechanisms. In the case of Ames, I think it’s fair to say that things weren’t actually that hard for Ames. When he fought Stanley, it was it wasn’t actually Stanley who picked that fight. Right? It was Ames. It was Ames who made a fool of himself, and a lot of Ames’s problems were that he thought: “Transition can solve things. I did the work of transition.” But what I think is that transition is just the first step in figuring this stuff out, making a stand, and not getting stuck. You have to constantly be honest with yourself. You can’t just transition and then be like, well, I did that hard part. That’s just the beginning.

I actually have a lot of empathy for Ames. I think that the negotiations that people have around selfishness are actually fair. Part of what I wanted to talk about is the fact that—after you transition—how are you actually going to live? How are you going to live in your middle age? Because while it’s fair to say, OK, there are not elders, blah, blah, and talk about role models in the abstract, or do you have community? But then there are the actual material ways of living, which is what I’m interested in. How do you provide for yourself? How do you do that in an ethical way? Do you work for a tech company? Do you get a job? Do you buy property? How do you save for retirement? A lot of the questions of transition ask who you’re going to love, these kind of things, like what are your ethics? What do you think? And like, those are fine questions, but what actually happens when you’re looking at 40 years of bills ahead of you? How are you going to live? And so when Ames says, basically this is too hard, he’s looking at a reality that a lot of people don’t think about with trans women. How are you going to make a sustainable life?

His detransition was a calculation of these sorts of things. He basically decides, in a way that you could say was cowardly, that “this is too hard for me. I see these other opportunities, and I can have these comforts and I can have the security. That’s what’s important to me.” Maybe that is cowardly, and certainly, those coping mechanisms fell apart over the course of the book. But part of what I want to do in this kind of writing, and why I think fiction works for me, is that I want to actually have characters behave selfishly and take that seriously. Not say, oh, they behave selfishly and so what they did is invalidated by that selfishness. To basically say, like, yeah, Ames behaved selfishly, great. Let’s actually take that for what it is, and let’s move from there, rather than just like condemn it and pretend like that’s not something people do.

For white trans women specifically, I think it was a real indictment of our frequent habit of not looking around us and seeing that our experiences are not singular. So many times in the book, I wanted to shake Ames and just say, “go to a community support meeting, like go to a drag show, go to something and find someone to talk to because my God, you are not the only person feeling like this!”

I agree! A lot of maturing as a trans person is having to realize your experience is actually quite banal.

Speaking of selfishness, there’s a moment when Reese and Thalia are at the drag show. Through Thalia, you write how a “baby trans woman,” to Thalia, “was complaining about how this woman looked at her at the store. That is how wounded she is, that she can’t take being looked at. Two eyes appraising her is trauma.” There are scenes like this in the book where trans women talk and act as if there are no cis people watching because at that moment there aren’t. Now there is this large cis audience reading your book, part of which you expected. How did you write through that quandary?

I mean, they’re just bitchy things I thought. At the time I wrote the book, I was largely surrounded by trans women. So if I wanted to say bitchy things about the people around me, they were going to be about trans women, right? My community actually was trans women, so if I wanted to talk shit, in the way that all the best writers talk shit, you talk shit about people you know, and that’s who I knew. And so I wasn’t going to pretend that I didn’t know these people. That’s who’s there to talk shit about. They’re lucky that I did it in fiction instead of on Twitter.

It goes back to this concept of messy, because I find that critics and wider audiences only ever apply that label to marginalized people. Fiction writing is people acting messy and somehow it’s only when a character is trans or otherwise that they describe them as messy.

All of my favorite books are like this. I reread Mary McCarthy’s The Group—it’s about Radcliffe. They’re like Radcliffe graduates or something—super prim Radcliffe graduates in the 30s. The stuff that they’re doing—getting married to like men in very normative ways—that was a book where the entire premise is watching these women be supremely messy and listening to the narrative voice just absolutely skewer them. It’s so enjoyable, and it’s like, I’m definitely going to do that, too, if it’s on the table for me.

You grapple with the concept of elders quite a lot in this book, but also your writing in general. I’m thinking of your novella, Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones. Through Reese, but also out in public, you’ve admitted that you feel like a mother to the girls, because there are so many new girls in Brooklyn that have said they transitioned in your orbit specifically. What was it like, the first time you felt like you were suddenly an elder in the community to people who were, frankly, older than you or the same age?

The nice thing about these cycles of transition is that they’re actually so short. You can come around again. I think when I wrote that book, I was annoyed at young trans people. I was a mother figure, and then I look back and think oh, even my irritation is actually part of a cycle. I’m thinking about the works of Morgan M Page and Zackary Drucker and Tourmaline, and the fact that so much really interesting trans art is about elders. I think Zackary’s movies are the first thing that really spoke to me this way. And every time I come back to them, they’ve already anticipated the stage that I’m in now. The art is itself replicating this process, and becomes almost a figure of an elder. It asks, “what does it mean to be an elder?” Instead of having to figure it out alone, I can look to Zackary and Tourmaline’s movies, or I can look to Morgan’s podcast.

The fact that I made a book that has something to do with trans mothers and trans elders, which at the time I was feeling very deeply, I can look back and be like, “oh, it’s just another work in a line of all of these other works, where there’s a stage trans women go through, where this is something that happens.” In that way, I see it in conversation with Zackary and Tourmaline and Morgan.

This brings up an interesting point: In recognizing that there were already blueprints out there for the cycles of life that trans women go through, how did you then grapple with the theme of dissociation, which plays heavily into the events of the book?

I remember when I was writing the book, I wrote the whole Glamour Boutique section about how it feels to be like a trans woman disassociating from your body during sex. I remember thinking that it was the most trans experience, like “this is so specifically trans to feel this way about your body.” At the time that I finished the book, within six months, the New Yorker published that Cat Person story, which was their most popular story ever. All these cis women on the internet said, “This is a story that says a thing that I’ve always experienced and never knew what it was.” I also read it and was like, this is an experience of dissociation during sex. That’s what this is. This experience that I thought was so trans is actually just a woman dissociating during sex. There are all sorts of reasons you might disassociate. The thing that I thought was so trans, and could only be understood by trans women, is in fact a widely understood experience. As long I wrote about it in terms of analogizing it, rather than saying this is how you must exactly feel, suddenly the experience of feeling disassociated with your body is actually a great way to talk about cis women’s experience of bad feelings during sex, and vice versa. It just opened up a lot of things, to cross boundaries through analogy.

The thing that I thought was so trans, and could only be understood by trans women, is in fact a widely understood experience

The interplay between cis women’s experiences and trans women’s experiences is so integral to the plot of the book, and also the characterizations. Katrina really acts as this foil between the two central trans people in this book. Ames asks her repeatedly, why did you get divorced? At first, it was about the miscarriage, but then it was really this something else, this disassociation the marriage induced in her. Reese also accuses Katrina, in reframing her divorce to be about queerness and disassociation, that she only wants “messy” parts of being trans. In a way, the same could be said of Reese about the pregnancy.

Part of the game I’m playing is asking, “What borders are you dissolving and what borders do you keep, shuffle around.” Even with Katrina saying, like, “I want all of the good parts of queerness without any of the hardship or bad stuff,” it’s like—girl, me too, join the club. Like, of course, I want all the cool things about transness without death and sadness and suicide and shit. Reese weaponizes that against her, but Reese also wants that. She fantasizes about butcher block tables and Cuisinarts mixers or whatever the fuck she wants. I think that that’s the dilemma of the world; we’re all constantly negotiating and navigating that stuff. What’s fun for me is dissolving the place of moral purity or righteousness. I feel like at the time I was writing this, I did want a punk-like utopia world of trans girls or whatever, at the same time that I really wanted a Cuisinart mixer.

For me, the ending of the book is: We could all just call each other hypocrites, and not do anything for the rest of our lives, and live in a state of stubbornness. Or you can admit it’s imperfect! We’re imperfect, our situation is imperfect. We can either live this cycle of perfectness over and over and over as we unravel, or we can take a chance on each other with all of our imperfections. I don’t know if the characters actually want to do that. I don’t want to even prescribe how to take a chance on people. I just say, this is the moment, and what if you take a chance.

I also see the battle between Reese and Katrina’s own sense of righteousness as a reproductive rights issue. Both Reese and Ames have frequent interactions with her where she says, no, wait, it is my body, it is my feelings. It is my ultimate decision about this pregnancy, not yours. I’m not a tool. It made me step back and say, I want a child. You know? I want a family, I want a kid. But what is it going to take for me to get that? And what kind of assumptions have I made about the process or the people that would have to be involved?

There isn’t a right answer. Reese’s sense of victimhood doesn’t actually extend to Katrina’s body. The ways that the world denies her opportunities, those are real, but it doesn’t actually give her a say over Katrina’s body. The kind of bodily autonomy that Reese fought for to have, and all of us trans women fought for to have, is the same bodily autonomy that needs to be protected for Katrina. There are so many nuances and there aren’t right answers. Fiction for me is a place to talk about the nuances over arguments about bodily autonomy, or trans rights. These concepts are sloganized as if it’s always easy: women should always have autonomy over their body, whether they’re trans or whether they’re cis. But what if there’s a situation that puts those two ideas at odds with each other, and how do we navigate that? It wasn’t a thinkpiece that could make these two things come together. The resolution for me had to do with emotional connections between individuals. There are so many of these intractable problems that actually can be at odds with each other. I don’t solve it with my brain; I feel it with my heart.

Reese’s change is a shift from whether or not she deserves a child, to the question of whether or not she deserves this child. The interplays of individuals break apart structures that we often rely on to like make our ethical decisions for us. She can tell herself that she deserves a baby, but it doesn’t mean that she necessarily deserves this baby.

It was really something to watch as the book played out because I have in my darkest moments thought to myself: How am I ever possibly going to get my hands on a baby, or my baby? I’ve had the idea—which is not something specific to me—that maybe a best friend come along who really also wants a child, and we can do the co-parenting thing, or maybe my husband and I can adopt. Maybe I can hold off long enough until they 3D print me a vagina and a uterus. Is that ethical? Is that something that I could morally stand by?

You know this, but I’m engaged now, and I will have a stepson. I wrote this whole book about an abstract child. Then, as soon as I finished it, I met somebody and she had a child and suddenly now, like, I have an actual child. I’m not quite a stepmom. But I have an actual child in my life, and there’s a part of me that almost wonders what I would have written if I had been this stepson as opposed to like the abstractions of a child. It’s like my life ended up accidentally charting the course of the book.